Runner’s Knee: Causes, Risks, and Recovery Options

Executive Summary

Runner’s knee (patellofemoral pain syndrome, PFPS) is one of the most common overuse injuries, affecting up to 30% of runners at some point. For athletes over 35, it’s even more prevalent due to age-related changes in cartilage, muscle imbalances, and slower recovery.

- What it is: Pain around or behind the kneecap, typically aggravated by running, squatting, stairs, or sitting with bent knees.

- Why it happens: Maltracking of the kneecap irritates cartilage. Aging athletes face added risks from declining proteoglycans, reduced GH/testosterone/NAD+, and decades of cumulative load.

- How to fix it: Physical therapy remains the gold standard, improving symptoms in 60–80% of cases within 12 weeks. Supplements, PRP, and regenerative peptides (BPC-157, TB-500, Ipamorelin, GHK-Cu, MOTS-c) can further accelerate healing by 20–40% in many cases.

- Surgery: Reserved for severe or persistent cases, with cartilage restoration techniques as a last resort.

- Prevention: Strength balance, smart periodization, and early intervention are key.

Bottom line: With layered strategies—traditional PT at the core, plus targeted nutrition and regenerative therapies—athletes over 35 can not only recover from runner’s knee but extend performance longevity well into midlife and beyond.

Introduction: More Than Just a “Runner’s Problem”

Runner’s knee, formally called patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), is one of the most common overuse injuries in sport. It accounts for nearly a third of knee-related medical visits in runners.

For athletes over 35, this condition isn’t just inconvenient—it can be the difference between competing and sidelining. The susceptibility rises with age, not only because of training volume but because of biological changes in joint health, slower recovery, and decades of accumulated stress.

What It Feels Like and Why It Happens

Runner’s knee presents as pain centered around or just behind the kneecap. The ache usually flares during climbing stairs, long runs, squats, or even sitting too long with bent knees.

The root issue is maltracking. The kneecap doesn’t slide smoothly through its groove on the femur, irritating cartilage and surrounding tissues. Over time, this irritation leads to swelling, stiffness, and the frustrating loss of performance consistency.

Why Older Athletes Are at Higher Risk

Cartilage and Aging

Cartilage changes structurally with age. The shock-absorbing proteoglycans decline by about 10–15% per decade after 30, leaving joints less resilient under training stress.

Muscle Imbalances

The inner quadriceps (VMO) tends to weaken relative to the outer quad. Research shows VMO activation delays of 15–25% in athletes with PFPS—just enough to throw off knee alignment during running or cycling.

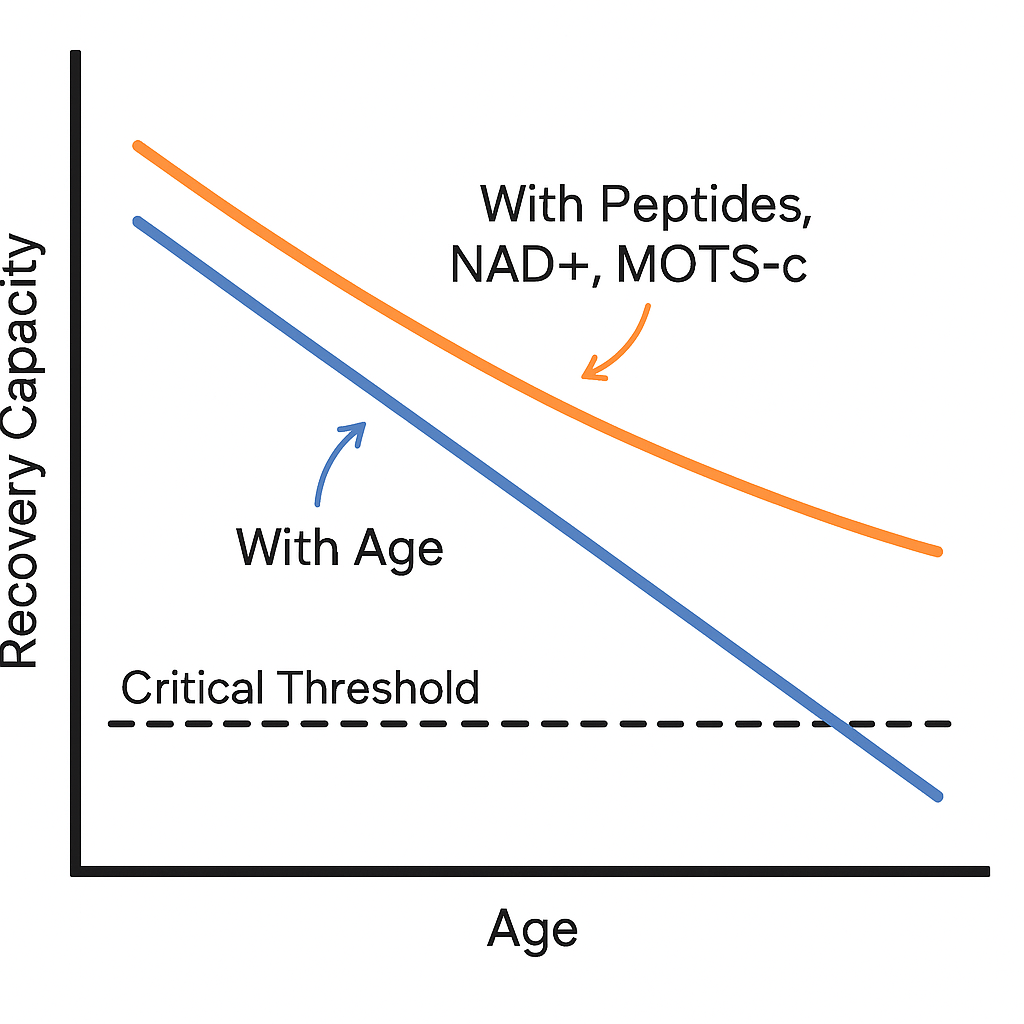

Recovery Threshold Decline

Hormonal and cellular energy factors also play a role. Growth hormone and IGF-1 fall 14% per decade, testosterone decreases about 1% annually in men over 35, and NAD+ levels drop by as much as 50% between ages 40 and 60. The combined effect is slower collagen synthesis and reduced tissue repair capacity.

Cumulative Load and Comorbidities

Years of training, small biomechanical flaws, and common issues like arthritis or hip stiffness further stack the deck. Each mile adds up, and by midlife the margin for error shrinks.

Tackling Recovery: From Rest to Rehab

The first step is usually simple: reduce or modify training load. Backing off long downhill runs or cutting mileage can calm symptoms within weeks. Ice, compression, and elevation help manage flare-ups, and patellar taping or bracing can immediately reduce activity-related pain by 25–30%.

But the foundation of long-term recovery is physical therapy. Strengthening the quadriceps—especially reactivating the VMO—has been shown to improve symptoms by 60–80% within 12 weeks. Adding hip and glute work improves outcomes even more, reducing pain scores by more than half in some trials. Stretching the hamstrings, IT band, and calves complements this, while running form adjustments like increasing cadence by 5–10% can drop joint stress by about 20%.

Nutrition and Supplement Support

For athletes over 35, rebuilding from the inside out is essential. Collagen combined with vitamin C boosts collagen synthesis by 20–25%, directly helping tendon and cartilage repair. Omega-3s lower systemic inflammation markers like CRP by 15–30%, while vitamin D and K2 support bone and joint health—critical since deficiencies are common in midlife athletes.

Medications and Injections: The Conventional Medical Route

Pharmaceutical options can offer relief, though their impact varies. NSAIDs ease discomfort but don’t speed healing. Corticosteroid injections reduce inflammation but repeated use accelerates cartilage breakdown. Hyaluronic acid injections like Synvisc or Euflexxa provide modest benefits—about 10–15% better than placebo. PRP, however, stands out: athletes receiving platelet-rich plasma recover 25–40% faster than those relying on PT alone.

Regenerative and Peptide Approaches

In recent years, regenerative medicine has opened new doors for athletes.

- BPC-157 has been shown to speed healing of tendons, ligaments, and cartilage by enhancing blood vessel growth and collagen remodeling.

- Thymosin Beta-4 (TB-500) accelerates tissue repair by about 30% in experimental models.

- Growth hormone secretagogues like Ipamorelin and CJC-1295 increase IGF-1, supporting collagen synthesis and joint recovery. Athlete protocols often use 100–200 mcg of Ipamorelin twice daily in a fasted state.

- GHK-Cu not only stimulates cartilage matrix proteins but also remodels scar tissue and reduces fibrosis risk.

- Mitochondrial enhancers like MOTS-c and NAD+ precursors raise recovery thresholds, cutting soft tissue recovery times by 25–40% in experimental models—particularly relevant for older athletes.

Surgical Options: When Nothing Else Works

Surgery should be the last resort, but it remains an option in stubborn cases. Arthroscopy can smooth damaged cartilage; lateral release procedures address patellar alignment problems. More advanced techniques—such as microfracture or autologous chondrocyte implantation—attempt to restore cartilage itself, typically reserved for athletes with severe or persistent damage.

Prevention and Long-Term Joint Health

The smartest play is prevention. Balanced strength training across quads, glutes, and calves ensures proper joint alignment. Periodized training avoids the pitfalls of constant overload. Supplements and peptides may serve as proactive measures for tissue resilience, especially in older athletes. And most importantly, treat kneecap pain early—pushing through discomfort often transforms a fixable problem into a chronic one.

Conclusion: Defying Father Time

Runner’s knee may be common, but it doesn’t have to be career-limiting. For athletes 35 and up, the combination of PT, smart nutrition, and newer regenerative tools offers more options than ever before.

The key is layering strategies—strength and therapy for the foundation, supplements and peptides to raise the recovery threshold, and advanced interventions if needed. With the right approach, athletes can heal injuries that once lingered for years, and keep stacking miles, races, and victories against Father Time.