The Two-Front War: A Modern Guide to Cardiovascular Longevity

Executive Summary

Heart health has long been treated as a simple cholesterol problem, but modern science shows the real issue is more complex — and more fixable.

Cardiovascular risk is best understood as a two-front challenge. One front is the number of harmful particles in the blood, measured by Apolipoprotein B (ApoB). The other is the condition of those particles, particularly whether they become oxidized and inflammatory once they enter artery walls.

The body has natural systems that remove cholesterol, repair blood vessels, and calm inflammation. These systems work best when metabolic conditions are favorable.

By improving insulin sensitivity, reducing excess particle production, limiting oxidative stress, and supporting vascular repair, modern metabolic and peptide-based strategies can help restore those conditions — often producing measurable improvements in blood markers within weeks.

Long-term success still depends on maintaining healthy habits. Diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management help preserve gains by keeping oxidative stress low and preventing new damage.

The future of cardiovascular longevity isn’t about one cholesterol number. It’s about addressing particle quantity and particle quality together to support lasting arterial health.

Part 1: The Quantity Problem (ApoB)

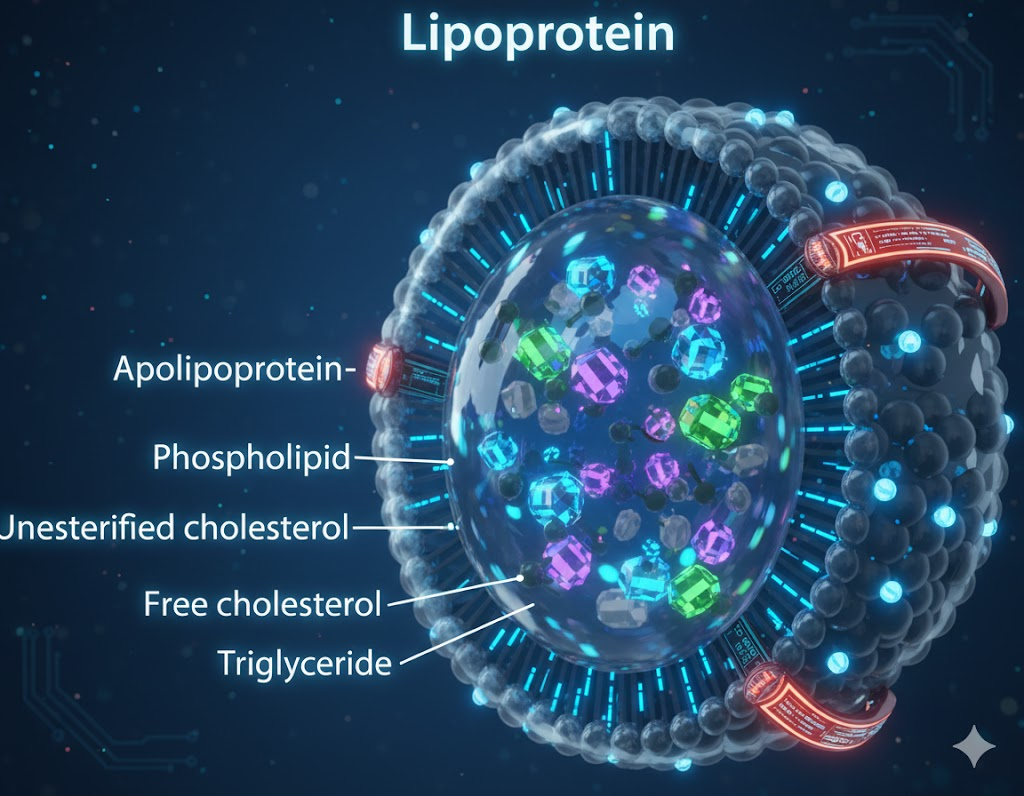

Every particle capable of contributing to a heart attack — LDL, VLDL, and Lipoprotein(a) — carries a single identifying protein called Apolipoprotein B (ApoB).³

This makes ApoB a simple but powerful concept: it tells you how many problem particles are on the road.

Think of your arteries as a highway. ApoB isn’t measuring how big the cars are. It’s counting how many are speeding through traffic.

Large genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies repeatedly show that ApoB predicts cardiovascular risk better than LDL cholesterol alone, because damage is driven by particle number, not just cholesterol content.⁴⁻⁶

When ApoB is high, more particles are circulating, more are slipping into artery walls, and plaque has more opportunities to form — even when standard cholesterol panels appear “normal.”⁷

Part 2: The Quality Problem (Oxidative Stress)

A high ApoB count increases risk — but real danger begins when those particles become oxidized.⁸

Oxidation is best thought of as rust.

When ApoB-containing particles lodge in the artery wall and undergo oxidative damage, the immune system no longer recognizes them as safe. White blood cells rush in to clean them up.

The problem is that these cells can’t process oxidized fat properly. They swell, malfunction, and become foam cells, which pile up and form plaque.⁹⁻¹¹

This process accelerates in people with insulin resistance, excess visceral fat, chronic inflammation, and poor cellular energy efficiency — all conditions strongly linked to higher oxidative stress.¹²⁻¹⁴

Clearing the Wreckage: How Your Body Repairs Damage

If your arterial highway is already littered with wreckage, how does cleanup happen?

The good news is that your body already has tow trucks and repair crews built in. Modern metabolic and peptide-based strategies don’t replace these systems — they create the conditions that allow them to work.

It’s important to set expectations: plaque stabilization and favorable changes in plaque activity can begin over weeks or months, particularly once new damage stops piling up and metabolic conditions improve.¹⁵

The Heavy Hitters: Dual and Triple Agonists (Tirzepatide & Retatrutide)

These compounds serve as Quantity Control tools.

Dual and Triple Agonists improve insulin sensitivity, reduce fat inside the liver, and significantly lower the liver’s output of VLDL particles — a major source of ApoB in circulation.¹⁶⁻¹⁸

Clinical trials consistently show reductions in ApoB, triglycerides, and other atherogenic particles alongside broad metabolic improvements.¹⁹⁻²¹

By reducing how many new particles enter circulation, these therapies give the body’s natural repair systems the time and metabolic bandwidth they’ve been missing.

The Built-In Tow Trucks: Reverse Cholesterol Transport (RCT)

Your body already has an elegant cleanup system.

Apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoA-1) and HDL particles remove cholesterol from foam cells and transport it back to the liver through a process called Reverse Cholesterol Transport.²²

Improving metabolic health doesn’t just reduce incoming debris — it also makes these tow trucks work more efficiently, even if HDL numbers themselves don’t change much.²³⁻²⁵

This means better cleanup, not just less mess.

The Highway Repair Crew: BPC-157 & TB-500

Once traffic slows and debris removal improves, the artery walls themselves need support.

Research suggests BPC-157 supports endothelial function and nitric oxide signaling, helping blood vessels remain flexible and responsive under stress.²⁶⁻²⁸

TB-500 (Thymosin Beta-4) has been shown to support cell movement and tissue repair in vascular and cardiac injury models.²⁹⁻³¹

These peptides don’t remove plaque. Instead, they help stabilize the arterial lining, reducing the chance that existing plaques rupture — the event that triggers most heart attacks.³²

The Antioxidant Bodyguard: GHK-Cu

GHK-Cu functions as rust prevention.

Studies show it increases protective antioxidant enzymes like Superoxide Dismutase and reduces oxidative stress signaling.³³⁻³⁵

It essentially “coats” ApoB particles, making them far less likely to oxidize and lowering levels of oxidized LDL — one of the most dangerous forms of cholesterol.³⁶

The Fire Extinguisher: KPV

KPV helps manage inflammation at the crash site.

Derived from α-MSH, KPV has been shown to quiet key inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB, and reduce excessive immune activation in stressed tissues.³⁷⁻³⁹

By cooling the inflammatory response, it helps prevent existing plaques from growing larger or becoming more unstable.

The Bonus Tool: Tesamorelin

While Dual and Triple Agonists are excellent for overall metabolic improvement, Tesamorelin can play a targeted role.

It specifically reduces visceral (deep organ) fat, which strongly fuels liver-driven lipoprotein production and elevated ApoB.⁴⁰⁻⁴³

Tesamorelin is most useful when ApoB remains elevated despite weight loss and metabolic improvement — acting more like a focused liver-support tool than a general fat-loss agent.

Maintaining the Win: Why Lifestyle Still Matters

Lowering ApoB, oxidation, and inflammation creates a powerful reset — but maintaining healthy conditions afterward is what preserves the gains.

Dietary patterns that stabilize blood sugar, regular physical activity that improves insulin sensitivity, adequate sleep, and stress management all help keep oxidative stress low and particle production controlled.⁴⁴⁻⁴⁷

In simple terms: once the highway is cleared and repaired, how you drive on it determines how long it stays that way.

Long-term cardiovascular health depends not only on intervention, but on maintaining the biological environment that prevents new damage from accumulating.

Summary: The 2026 Perspective

Heart health is no longer about chasing a single cholesterol number.

It’s about reducing excess particle traffic, preventing particles from becoming dangerous, supporting natural cleanup, strengthening vessel walls, calming unnecessary inflammation — and sustaining healthy conditions over time.

Some tools discussed here are long-established in clinical medicine, while others come from emerging research. What unites them isn’t regulatory category — it’s biological logic.

When both quantity and quality are addressed together, the body regains the conditions it needs to stabilize, repair, and protect the cardiovascular system long term.

References

- Steinberg D. The LDL cholesterol hypothesis of atherosclerosis: an update. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(11):2197–2203.

- Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874.

- Sniderman AD, et al. Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2019;321(24):2441–2442.

- Ference BA, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–2472.

- Wilkins JT, et al. Discordance between LDL-C and ApoB. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):193–201.

- Pencina MJ, et al. Apolipoprotein B improves risk prediction. Circulation. 2015;132(23):2185–2194.

- Mora S, et al. LDL particle number and risk. Circulation. 2007;116(10):1188–1197.

- Stocker R, Keaney JF. Oxidative stress and atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(4):1381–1478.

- Steinberg D. Oxidized LDL and foam cell formation. Circulation. 1997;95(4):1062–1071.

- Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145(3):341–355.

- Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407(6801):233–241.

- Furukawa S, et al. Oxidative stress in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1752–1761.

- Brownlee M. Biochemistry of hyperglycemia. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–820.

- Ungvari Z, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and vascular aging. Am J Physiol. 2008;295(4):H1448–H1455.

- Nicholls SJ, et al. Plaque stabilization and regression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):590–597.

- Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of GLP-1–based therapies. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740–756.

- Sattar N, et al. Tirzepatide metabolic effects. Lancet. 2022;399(10321):151–164.

- Jastreboff AM, et al. Retatrutide phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:514–526.

- Bays HE, et al. Lipoprotein changes with GLP-1 therapy. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(9):2406–2413.

- Kosiborod M, et al. GLP-1 agonists and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):2877–2888.

- Pratley R, et al. Cardiometabolic outcomes of incretin therapies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(1):3–18.

- Rader DJ. HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):659–672.

- Kontush A. HDL functionality. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(10):632–642.

- Rosenson RS, et al. HDL quality vs quantity. Circulation. 2016;134(10):e234–e237.

- Shah AS, et al. Insulin resistance and HDL dysfunction. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(3):733–743.

- Sikiric P, et al. BPC-157 and vascular effects. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69(4):473–486.

- Hsieh MJ, et al. BPC-157 endothelial signaling. Biomaterials Science. 2022;10(4):112–125.

- Seiwerth S, et al. BPC-157 and nitric oxide pathways. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(16):1612–1632.

- Goldstein AL, et al. Thymosin beta-4 and tissue repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1112:89–96.

- Smart N, et al. Thymosin beta-4 and cardiac repair. Nature. 2007;445(7124):177–182.

- Bock-Marquette I, et al. TB-4 in vascular injury. Circ Res. 2004;94(6):e51–e59.

- Virmani R, et al. Plaque rupture mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8 Suppl):C13–C18.

- Pickart L. GHK-Cu and tissue remodeling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;152:33–42.

- Siméon A, et al. GHK-Cu gene expression effects. FASEB J. 2010;24(10):3642–3651.

- Maquart FX, et al. Copper peptides and oxidative stress. Pathol Biol. 1993;41(7):601–606.

- Brewer HB. Oxidized LDL and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Lipidol. 2008;2(6):363–369.

- Getting SJ, et al. KPV anti-inflammatory signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289(3):1521–1526.

- Patel HB, et al. α-MSH peptides and NF-κB suppression. Endocrinology. 2010;151(8):3690–3698.

- Catania A, et al. Melanocortin peptides and inflammation. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(4):564–585.

- Falutz J, et al. Tesamorelin and visceral fat. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1159–1168.

- Stanley TL, Grinspoon SK. Growth hormone axis and visceral adiposity. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(6):655–683.

- Koutkia P, et al. Tesamorelin metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1019–1028.

- Després JP. Visceral fat and cardiometabolic risk. Circulation. 2012;126(10):1301–1313.

- Estruch R, et al. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):e34.

- Lear SA, et al. Physical activity and cardiovascular health. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2643–2654.

- St-Onge MP, et al. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic health. Circulation. 2016;134(23):e367–e386.

- Rosengren A, et al. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9436):953–962.