Peeing Like a Racehorse Again

The Science of Flow, TRT Myths, and Prostamax

Executive Summary (Plain-English Version)

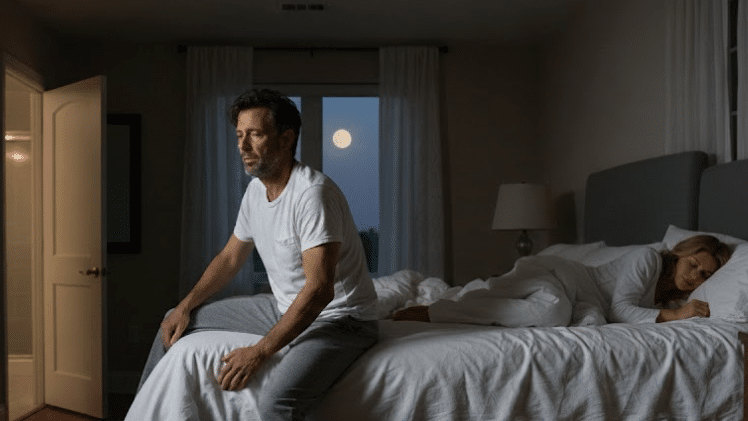

As men age, many notice a frustrating change in their bathroom habits—waking up multiple times at night to urinate, feeling urgency during the day, or experiencing a weak or interrupted stream. These issues are most often caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate that affects the majority of men over 50.¹

For years, the standard medical approach has focused on either blocking hormones (such as DHT) or relaxing smooth muscle around the prostate. While these strategies can help some men, they often come with tradeoffs—particularly sexual side effects or benefits that disappear as soon as treatment stops.

This article explains:

- Why BPH develops with age, and how hormonal signaling—not just prostate size—drives symptoms

- Why testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) is no longer automatically considered dangerous for men with prostate enlargement

- Why medications like finasteride work—but sometimes at a cost

- How peptide bioregulators such as Prostamax differ fundamentally from drugs and herbal supplements

Instead of suppressing hormones or forcing short-term symptom relief, Prostamax has been studied as a biological signaling peptide—one that may help aging prostate tissue behave more normally by reducing inflammation, improving micro-circulation, and supporting healthier tissue structure.

While Prostamax is not FDA-approved and should be viewed through an educational and research lens, decades of peptide bioregulator research offer a compelling alternative framework: supporting tissue health and signaling, rather than simply blocking hormones or masking symptoms.

The Silent Growth: What Causes BPH?

The prostate gland surrounds the urethra like a collar. As it enlarges, it gradually compresses the urinary channel—much like bending a garden hose—reducing flow and increasing resistance.¹

At the biological level, BPH appears to be driven by age-related hormonal signaling changes, particularly involving dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT is a potent metabolite of testosterone that strongly stimulates prostate cell growth. As men age, prostate tissue becomes increasingly sensitive to DHT, leading to slow but progressive enlargement over time.³⁻⁵

Common symptoms include:

- Nocturia – waking multiple times per night to urinate

- Urgency and frequency – sudden, difficult-to-delay urges with a weak stream

- Incomplete emptying – a persistent feeling that the bladder never fully empties¹

Although rarely dangerous, these symptoms significantly impact sleep, energy, confidence, and daily quality of life.²

The Standard Drug Approach: Finasteride—and the Tradeoffs

One of the most commonly prescribed medications for BPH is finasteride (5 mg), a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor that lowers DHT production. By reducing DHT-driven signaling, finasteride can gradually shrink prostate volume and reduce the risk of urinary retention or surgery in some men.⁶

The tradeoff is that DHT is not exclusive to the prostate. It also plays a role in libido, erectile signaling, and sexual sensitivity. Clinical data show dose-dependent and expectation-dependent sexual side effects, including erectile dysfunction (ED).⁶⁻⁸

Reported ED Rates by Context

| Context | Reported ED Rate |

| Hair loss trials (1 mg) | ~1.5%–4%⁷ |

| BPH treatment (5 mg) | ~8%–15%⁶ |

| Explicitly warned about sexual side effects (nocebo effect) | ~30.9%⁸ |

| Placebo groups | ~1%–2%⁶⁻⁷ |

A subset of men report persistent sexual symptoms after discontinuation, sometimes referred to as post-finasteride syndrome. While prevalence and causality remain debated, this possibility has influenced many men—particularly those already concerned about libido or erectile function—to seek approaches that do not rely on androgen suppression.⁹⁻¹¹

TRT and the Prostate: Myth vs. Modern Reality

For decades, men with BPH were routinely warned to avoid testosterone replacement therapy (TRT). The prevailing concern was simple: increasing testosterone would increase DHT, which would “fuel the fire” and accelerate prostate growth.¹²

Modern urology has since moved toward a more nuanced understanding known as the Saturation Model. This model suggests that androgen receptors in prostate tissue become fully saturated at relatively low testosterone levels. Once saturation occurs, additional testosterone does not meaningfully increase prostate stimulation.¹³

Some studies even suggest that TRT may improve urinary symptoms in certain men by reducing pelvic inflammation, improving vascular tone, and enhancing bladder muscle function—helping the “pump” work more efficiently even if the “pipe” remains partially narrowed.¹⁴⁻¹⁶

This does not mean TRT is universally beneficial for every man with BPH, but it does mean the once-absolute prohibition is no longer scientifically justified.

A Different Approach: Bioregulation and Prostamax

As the limitations of both hormone suppression and surgical intervention become clearer, interest has shifted toward approaches that work with tissue biology rather than against it.

Prostamax was developed in Russia as part of a broader research program focused on cytomedins—short, organ-specific peptides designed to regulate tissue structure, inflammation, and cellular repair. Cytomedins were originally isolated from animal tissues and later synthesized as precise amino-acid sequences for experimental and clinical research.¹⁷⁻¹⁹

Importantly, Prostamax research has focused on inflammation, tissue organization, and cellular signaling—not androgen suppression or acute prostate shrinkage.

Observed Actions in Research Models

Based on historical Eastern European research, Prostamax has been observed to:

- Support prostate epithelial structure and function¹⁸

- Reduce local inflammatory signaling and swelling¹⁹

- Improve micro-circulation within prostate tissue²⁰

- Influence connective tissue remodeling and reduce fibrotic stiffening²¹

These effects differ from botanical supplements, which primarily aim to blunt androgen activity or temporarily mask symptoms rather than influence cellular signaling directly.

Historical Research Protocols (Educational Context Only)

| Protocol Type | Observed Dose | Duration | Research Focus |

| Standard | 0.5–1 mg/day | 10–20 days | Tissue normalization |

| Moderate / Extended | 1–2 mg/day | 20–30 days | Structural and inflammatory support |

| Exploratory High Range | 2–3 mg/day | 10–15 days | Glandular overgrowth models |

| Maintenance | 0.5 mg (2–3×/week) | 4–6 weeks | Long-term stability |

Across multiple models, lower doses tended to stabilize cellular behavior, while longer or higher-dose protocols were associated with changes in tissue density and organization.¹⁸⁻²¹

Observational & Anecdotal Outcomes (Non-Clinical)

In community forums and observational reports, users most frequently describe a consistent pattern of improvements. These reports are not clinical trial data, but they are notable for their specificity, repeatability, and alignment with the proposed bioregulatory mechanisms of Prostamax.

1. Reduced Nocturia

Often described as the most “life-changing” effect, users frequently report a dramatic reduction in nighttime bathroom trips. Many describe moving from 3–5 awakenings per night to 0–1 within the first two weeks of a cycle.

2. Improved Urinary Flow (“Strength of Stream”)

Many users note a stronger, more consistent urinary stream. This is often described as a sensation that pelvic pressure or physical obstruction has eased, allowing urine to pass more freely rather than trickling or stopping and starting.

3. Resolution of Lingering Discomfort

Men with chronic, non-bacterial prostatitis or long-standing prostate irritation frequently report the reduction or disappearance of a dull ache, pressure, or heaviness in the perineal region. This pattern is consistent with research findings showing reduced swelling, lymphoid infiltration, and inflammatory signaling within prostate tissue.

4. Secondary Vitality Effects

While Prostamax is not a testosterone booster, some users report secondary improvements in morning erections, sexual interest, and overall vitality. In animal research models, this was described as an intensification of sexual activity, likely linked to restoration of normal prostate secretory function rather than direct hormonal stimulation.

The “Subtle Start” Phenomenon

Unlike pharmaceutical alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin—which can produce noticeable effects within hours—users of peptide bioregulator protocols often describe a distinct onboarding pattern:

- Days 1–4: Typically no noticeable change

- Days 5–10: Gradual realization of fewer nighttime awakenings or reduced urgency

- Post-Cycle Persistence: Benefits often persist 3–6 months after a short cycle, a feature users frequently contrast with herbal supplements that stop working immediately when discontinued

Reported side effects are generally minimal, aligning with the bioregulator profile of low toxicity at studied doses and the absence of systemic hormonal suppression.

Conclusion

BPH may be nearly universal, but the way it is understood—and approached—is evolving.

The relationship between TRT and prostate health is far more nuanced than once believed, and blanket avoidance is no longer supported by modern evidence. At the same time, peptide bioregulators such as Prostamax offer a biologically intelligent framework—one that prioritizes tissue signaling, inflammation control, and structural maintenance rather than blunt hormonal suppression.

While Prostamax is not FDA-approved, decades of cytomedin research provide a compelling conceptual foundation for those exploring prostate health at the cellular level—particularly in the context of aging, inflammation, and long-term tissue resilience.

Reference List:

- Roehrborn CG. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an overview. Rev Urol. 2005;7(Suppl 9):S3-S14.

- McVary KT. Clinical evaluation of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol. 2003;5(Suppl 5):S3-S11.

- Wilson JD. The role of dihydrotestosterone in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1980;16(5):524-528.

- Bartsch G, Rittmaster RS, Klocker H. Dihydrotestosterone and the prostate. Urology. 2000;55(6):12-18.

- Carson C, Rittmaster R. The role of dihydrotestosterone in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2003;61(4 Suppl 1):2-7.

- Proscar® (finasteride) prescribing information. Merck & Co; 2014.

- Propecia® (finasteride) prescribing information. Merck & Co; 2012.

- Mondaini N, et al. Finasteride 5 mg and sexual side effects: the nocebo phenomenon. J Sex Med. 2007;4(6):1708-1712.

- Traish AM, et al. Post-finasteride syndrome. Sex Med Rev. 2015;3(2):65-76.

- Belknap SM, et al. Persistent erectile dysfunction associated with finasteride. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3020.

- Khera M. Persistent sexual side effects of finasteride. J Sex Med. 2016;13(5):803-804.

- Morgentaler A. Testosterone therapy and prostate cancer risk. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43(2):209-216.

- Morgentaler A, Traish AM. Shifting the paradigm of testosterone and prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55(2):310-320.

- Yassin A, et al. Testosterone therapy improves urinary symptoms. World J Urol. 2014;32(4):1049-1054.

- Haider A, et al. Effects of long-term testosterone therapy on LUTS. Aging Male. 2018;21(1):1-9.

- Kohn TP, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4(2):179-185.

- Khavinson VK. Peptide Bioregulators: 30 Years of Clinical Use. St. Petersburg; 2004.

- Khavinson VK, Trofimova SV. Short Peptides and Gerontology. 2002.

- Morozov VG, Khavinson VK. Clinical experience with prostate peptide fractions in men over 50. 2000.

- Bondarev IE, Khavinson VK. Peptide extracts in experimental models of glandular degeneration. Exp Biol Med. 1997;124(3):57-63.

- Trofimova SV, Khavinson VK. Long-term modulation of prostate tissue using short peptides. Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;15(4):33-40.