Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, Immune Misfiring, and the Role of Peptides in Restoring Immune Balance

Executive Summary

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common autoimmune disease worldwide, yet it is frequently approached as a purely hormonal disorder. While declining thyroid hormone output is a defining feature, the initiating driver is not endocrine failure—it is chronic immune dysregulation.

In Hashimoto’s, the immune system misidentifies thyroid tissue as a persistent threat, generating ongoing inflammatory signaling that gradually compromises the gland. Standard treatment strategies focus primarily on hormone replacement, which may alleviate symptoms but does not address the upstream immune signaling errors that initiate and perpetuate the disease.

This article reframes Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as a condition rooted in failed immune resolution rather than immune excess. It explores how cytokine imbalance, regulatory T-cell dysfunction, immune memory imprinting, and cumulative immune strain contribute to thyroid injury over time. Within this framework, the article examines how immunomodulatory peptides, particularly Thymosin Alpha-1, alongside supportive peptides such as KPV, BPC-157, Thymosin Beta-4, and GHK-Cu—including combination strategies such as KLOW—may help guide immune signaling back toward stability while supporting tissue resilience once immune pressure has been reduced.

When the Immune System Targets the Thyroid

In healthy physiology, the thyroid gland operates under tight feedback control, responding dynamically to metabolic demand. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, this balance is gradually undermined—not by sudden failure, but by years of immune miscommunication.

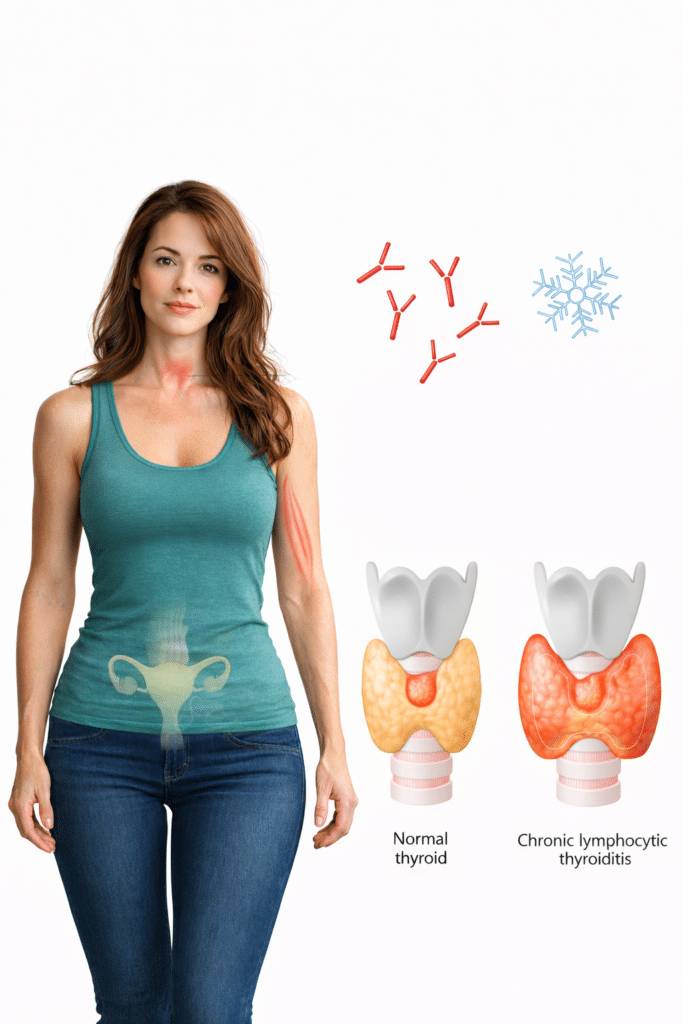

Autoreactive immune cells infiltrate thyroid tissue, producing antibodies such as anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin (Tg). These antibodies are not inherently destructive; rather, they are markers of an immune system that has failed to properly terminate an inflammatory response. Over time, repeated immune activation leads to tissue injury, altered architecture, and diminished hormone-producing capacity.¹

Many individuals experience fluctuating symptoms—fatigue, cold intolerance, cognitive fog, mood changes, or weight instability—that often fail to correlate cleanly with laboratory values. These fluctuations frequently reflect ongoing immune activity, not simply hormone deficiency.

Hashimoto’s Along the Spectrum of Immune Dysregulation

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis occupies a specific position along the immune-dysregulation spectrum.

Unlike acute autoimmune flares characterized by explosive cytokine release, Hashimoto’s more commonly presents as persistent, low-grade immune activation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α may remain elevated, while counter-regulatory signals fail to fully engage.²

This pattern reflects immune persistence rather than immune aggression. The immune system remains partially activated, repeatedly sampling thyroid antigens without successfully resolving the response. Over time, immune tolerance erodes, and thyroid tissue becomes a standing target rather than a resolved event.³

This slow, smoldering inflammation explains why Hashimoto’s may progress silently for years before clinical hypothyroidism becomes apparent—and why symptom burden often persists even after hormone levels are normalized.

Why Immune Dysregulation Develops Over Time

Hashimoto’s rarely arises from a single trigger. Instead, it reflects cumulative strain on immune regulatory capacity.

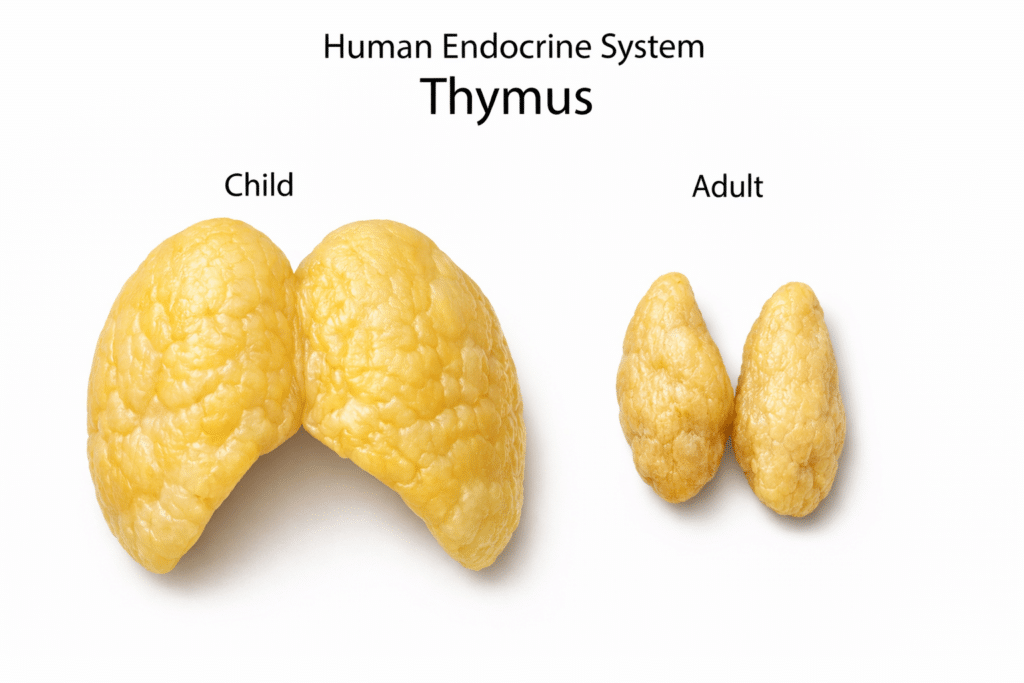

One major contributor is age-related thymic involution. As thymic output declines, fewer naïve and regulatory T cells are produced, reducing immune precision and tolerance. The immune system becomes increasingly biased toward memory responses, including autoreactive patterns.⁴

Chronic stress further accelerates this process. Psychological stress, metabolic strain, sleep disruption, and sustained physical stress alter cytokine signaling and impair immune shutdown mechanisms. Over time, this biases the immune system toward persistent activation.⁵

Environmental exposures compound immune load. Iodine excess, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, dietary antigens, and microbial stimuli can repeatedly activate immune pathways linked to thyroid antigens, reinforcing immune misidentification rather than tolerance.⁶

Infections may serve as inflection points. Viral and bacterial exposures can leave long-lasting imprints on immune signaling through molecular mimicry, maintaining autoreactive immune memory long after the infection has resolved.⁷

Gut barrier integrity also plays a central role. Increased intestinal permeability allows persistent immune stimulation that amplifies systemic inflammatory tone and lowers the threshold for autoimmune activity in distal tissues, including the thyroid.⁸

Taken together, these influences gradually reduce immune resolution capacity. Hashimoto’s therefore represents not a sudden immune failure, but the predictable outcome of long-term strain on immune regulation.

Immunomodulation vs Hormonal Replacement

Thyroid hormone replacement addresses a downstream consequence of Hashimoto’s but does not modify immune behavior. Many individuals remain symptomatic despite normalized laboratory values, reflecting unresolved immune signaling rather than inadequate hormone dosing.

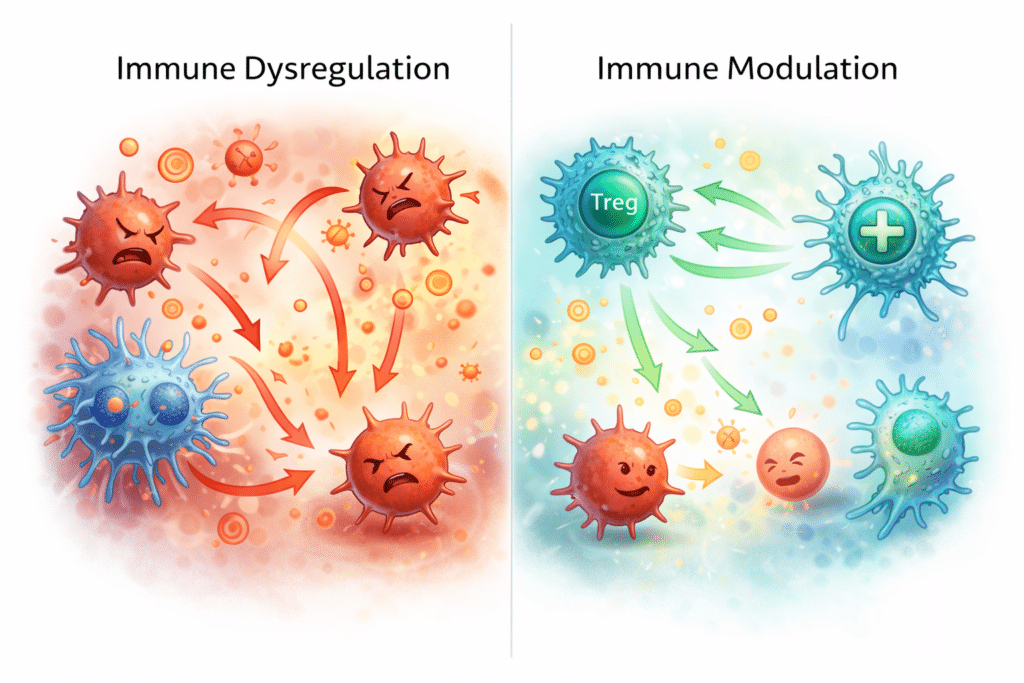

Immunomodulation takes a different approach. Rather than suppressing immune activity or forcing endocrine compensation, it aims to restore proportional immune signaling—allowing inflammatory responses to occur when appropriate and resolve when their function is complete.

This upstream focus on immune regulation is central to understanding the role of Thymosin Alpha-1.

Thymosin Alpha-1 and Immune Re-Calibration

Thymosin Alpha-1 (TA-1) is a naturally occurring thymic peptide involved in immune coordination and tolerance signaling. It is best understood as an immune educator, influencing how immune responses initiate, differentiate, and resolve rather than acting as a direct anti-inflammatory agent.⁹

One of its most relevant actions in autoimmune contexts involves regulatory T cells, which serve as the immune system’s internal braking mechanism. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, regulatory signaling is often impaired, allowing autoreactive immune cells to persist. TA-1 has been shown to enhance regulatory T-cell function and restore immune resolution capacity.¹⁰

TA-1 also modulates inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB and interferon-driven cascades. Rather than fully inhibiting these pathways, it appears to influence their activation dynamics—reducing background inflammatory tone while preserving immune defense.¹¹

Additionally, TA-1 supports dendritic cell differentiation toward more tolerogenic phenotypes, helping shift immune interpretation of thyroid antigens away from threat recognition and toward immune neutrality.¹²

For these reasons, TA-1 is best viewed as a foundational phase in immune-focused strategies for Hashimoto’s.

When Local Signal Control Is Sufficient: TA-1 and KPV

In some individuals, immune dysregulation is present without clear evidence of long-standing structural thyroid damage. Symptoms may suggest persistent inflammatory “noise” rather than entrenched tissue compromise.

In these cases, pairing TA-1 with KPV may represent a more proportionate strategy than escalating immediately to broader repair-oriented combinations.

KPV functions at the interface of immune signaling and tissue response. It has been shown to reduce localized cytokine signaling without suppressing immune defense, making it particularly relevant when residual inflammation persists after immune modulation has begun.¹³

Within this framework:

- TA-1 addresses systemic immune coordination and resolution

- KPV helps quiet ongoing tissue-level inflammatory signaling

This combination allows immune recalibration to proceed while minimizing unnecessary escalation into full tissue repair strategies when they may not yet be biologically warranted.

When Repair Becomes the Bottleneck: The Role of KLOW

In longer-standing Hashimoto’s, immune dysregulation is often accompanied by structural and metabolic consequences within thyroid tissue. Reduced microcirculation, altered extracellular matrix organization, and fibrotic remodeling may become limiting factors even after immune signaling begins to normalize.

In these cases, immune modulation alone may reduce inflammatory pressure without fully restoring tissue resilience. This is where KLOW, a combination of KPV, BPC-157, Thymosin Beta-4, and GHK-Cu, becomes relevant.

KLOW is not an immune-training strategy. Instead, it operates downstream of immune signaling, addressing the consequences of prolonged inflammation:

- KPV moderates residual inflammatory signaling

- BPC-157 supports angiogenesis and epithelial integrity

- Thymosin Beta-4 facilitates cell migration and coordinated repair

- GHK-Cu influences collagen organization and extracellular matrix remodeling

For this reason, KLOW is best introduced after immune pressure has softened, or alongside immune modulation in cases where tissue compromise and immune dysregulation are clearly intertwined.

Sequencing Matters: Why Immune Regulation Comes First

Across these strategies, one principle remains consistent:

immune signaling should be addressed before, or alongside, tissue repair—not after it.

Attempting aggressive repair while immune misfiring persists may limit effectiveness or prolong recovery timelines. A staged approach—beginning with immune recalibration, followed by signal moderation, and escalating to tissue support only when needed—respects biological order rather than forcing outcomes.

Restoring Tolerance Rather Than Silencing the System

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is rarely the result of an immune system that is simply “too strong.” More often, it reflects a system that has lost precision, tolerance, and resolution capacity.

Within this framework, peptide-based strategies do not function as blunt suppressors. Instead, they act as biological signals—supporting immune re-education, proportional response, and downstream tissue resilience once immune pressure has been reduced.

References

- McLeod DS, Cooper DS. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity. Endocrine. 2012.

- Antonelli A, et al. Cytokine involvement in autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid. 2006.

- Rose NR. Prediction and prevention of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2016.

- Palmer DB. The effect of age on thymic function. Front Immunol. 2013.

- Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014.

- Winther KH, et al. Iodine and autoimmune thyroid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017.

- Smatti MK, et al. Viruses and autoimmunity. Clin Immunol. 2019.

- Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012.

- Garaci E, et al. Thymosin alpha 1: mechanism of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012.

- Romani L, et al. Thymosin alpha 1 activates regulatory T cells. Blood. 2006.

- Goldstein AL, et al. Immunoregulatory properties of thymosin alpha 1. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014.

- King R, et al. Thymosin alpha 1 and dendritic cell function. Clin Immunol. 2015.

- Brzoska T, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of KPV. J Invest Dermatol. 2008.

- Sikiric P, et al. BPC-157 and tissue healing. Curr Pharm Des. 2011.

- Goldstein AL, et al. Thymosin beta-4 in tissue repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012.

- Pickart L. The human tripeptide GHK and tissue remodeling. Biomed Res Int. 2015.