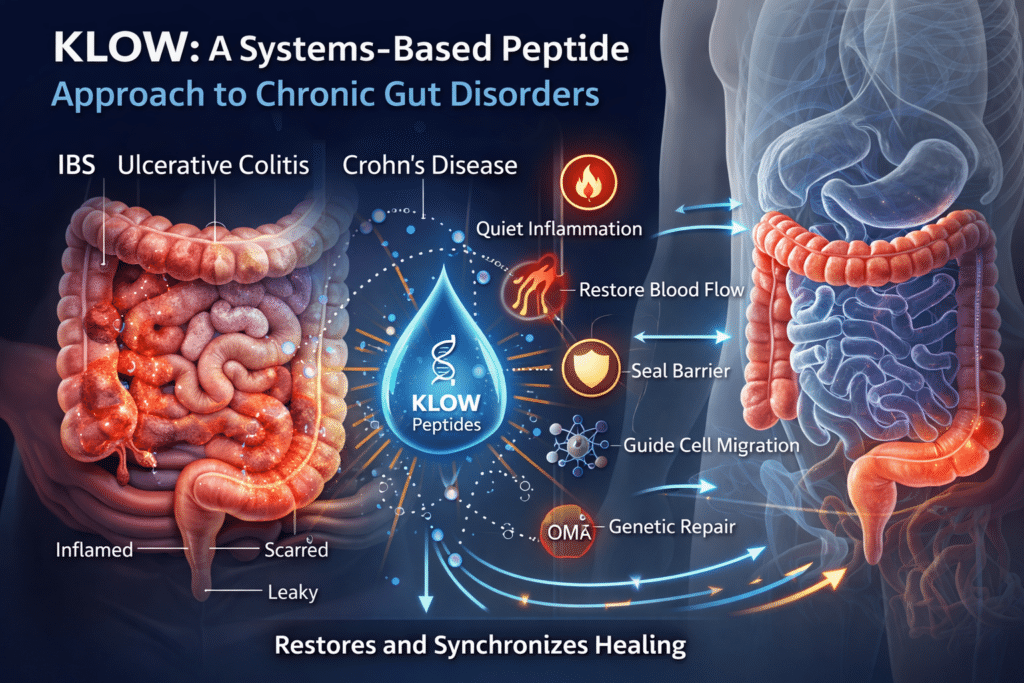

KLOW: A Systems-Based Peptide Approach to Chronic Gut Disorders

Executive Summary

Chronic gastrointestinal conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease are commonly described as inflammatory disorders. At a deeper biological level, however, they share a more fundamental problem: the gut loses its ability to complete the full healing cycle.¹⁻³

In chronic disease states, blood flow is reduced, the intestinal barrier remains compromised, inflammatory signaling stays locked in the “on” position, repair cells struggle to migrate effectively, and tissue often rebuilds improperly—either too fragile or excessively scarred.⁴⁻⁶ Importantly, this does not mean the body has lost the ability to heal. Rather, it becomes biologically constrained, trapped in a prolonged survival mode where damage is contained but never fully resolved.⁷

The peptide blend known as KLOW was designed around this reality.

Peptides do not force healing or override the immune system. Instead, they restore missing or degraded biological signals that normally coordinate repair. By relieving key repair bottlenecks and re-synchronizing the natural order of healing—quieting inflammation, restoring blood flow, sealing the epithelial barrier, guiding cell migration, and normalizing genetic repair programs—KLOW helps recreate the internal conditions required for healing to complete more effectively than it often can on its own in chronic gut disease.⁸⁻¹¹

Why Chronic Gut Conditions Struggle to Heal (The Shared Failure Pattern)

In a healthy gut, injury triggers a predictable sequence: inflammation contains damage, blood flow increases, epithelial cells migrate to cover wounds, tight junctions In a healthy gut, injury triggers a predictable sequence: inflammation contains damage, blood flow increases, epithelial cells migrate to cover wounds, tight junctions reseal, and tissue rebuilds to full strength. In chronic gut disease, this sequence stalls midway.

Barrier integrity fails, allowing luminal antigens to provoke immune activation.¹²

Inflammation remains chronically active instead of resolving.¹³

Blood supply is impaired, starving tissue of oxygen and nutrients.¹⁴

Repair cells migrate slowly or incompletely.¹⁵

Tissue rebuilds improperly, resulting in fragility or fibrosis.¹⁶

As a result, the gut remains locked in defense mode and never fully transitions back into reconstruction mode. KLOW is structured to address this entire failure loop rather than targeting a single downstream symptom.

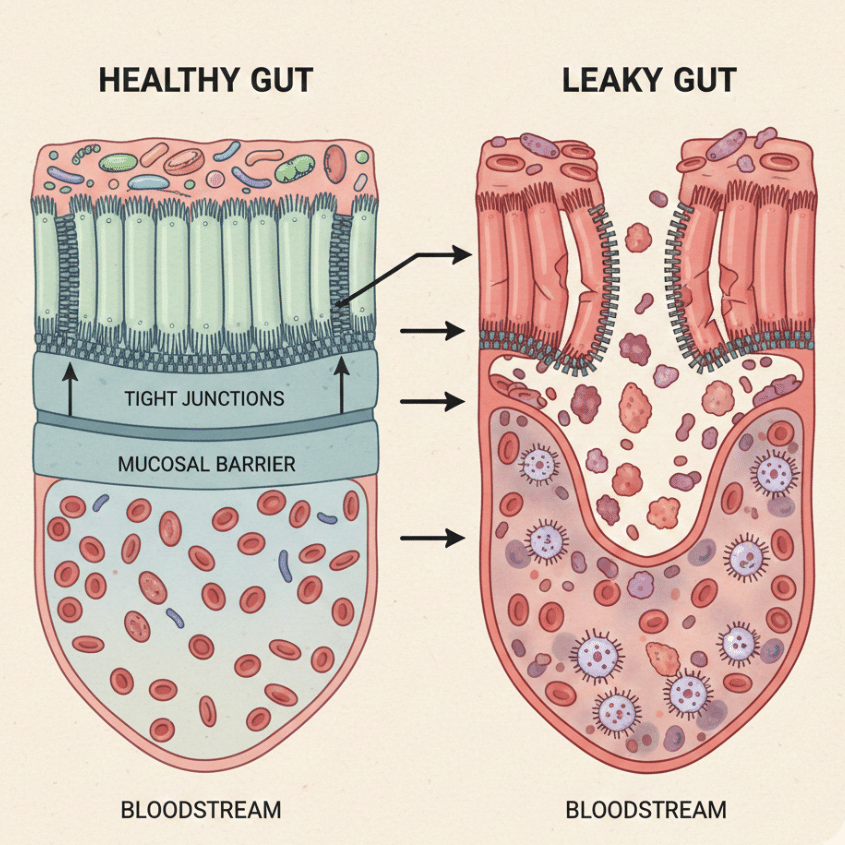

Leaky Gut: A Symptom of Incomplete Healing, Not a Diagnosis

“Leaky gut” refers to increased intestinal permeability—a state in which tight junctions between epithelial cells fail to fully seal, allowing bacterial fragments, dietary antigens, and inflammatory signals to cross the intestinal barrier and provoke immune activation.¹²,¹⁷

Leaky gut is not a disease itself, nor is it limited to any single diagnosis. Instead, it represents a shared downstream consequence of chronic gut injury seen in IBS, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease.

In healthy tissue, barrier disruption is temporary and resolves once healing is complete. In chronic disease, reduced blood flow, persistent inflammation, impaired cell migration, and maladaptive rebuilding prevent tight junctions from fully restoring—even during symptom remission. The gut may feel better but remain biologically compromised.

From a systems perspective, leaky gut reflects a failure of resolution rather than simple excess permeability.

IBS vs Colitis vs Crohn’s: Same Failure, Different Depths

IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome)

IBS is primarily a functional disorder involving subtle barrier dysfunction, low-grade immune activation, and dysregulated gut–brain signaling rather than overt tissue destruction.¹⁸⁻²⁰

Primary needs: barrier integrity, inflammation modulation, nervous system stabilization

Most relevant peptides: BPC-157, KPV

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis involves continuous surface-level inflammation confined to the colonic mucosa.²¹⁻²³ Healing depends heavily on epithelial turnover, angiogenesis, and tight-junction restoration.

Primary needs: inflammation control, mucosal repair, structured rebuilding

Most relevant peptides: BPC-157, KPV, GHK-Cu

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease involves full-thickness bowel injury with patchy distribution and a high risk of fibrosis and strictures.²⁴⁻²⁶

Primary needs: inflammation control, cell migration, anti-fibrotic guidance, genetic normalization

Most relevant peptides: all four components of KLOW, particularly TB-4 and GHK-Cu

1. BPC-157: The Master of Mucosal Integrity

BPC-157 is a synthetic fragment of a naturally occurring protective protein found in human gastric juice and plays a central role in maintaining gastrointestinal integrity.²⁷

Angiogenesis and Blood Flow Restoration

Chronically inflamed gut tissue frequently suffers from microvascular impairment. BPC-157 stimulates VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, restoring microcirculation and improving oxygen and nutrient delivery required for repair.²⁸⁻³¹

The Tight Junction “Ziploc”

Tight-junction proteins act like a zipper sealing epithelial cells together. When disrupted, immune activation follows. BPC-157 stabilizes and restores tight-junction architecture, resealing the barrier and reducing immune provocation at its source.³²⁻³⁷

Gut–Brain Axis Stabilization

By restoring barrier integrity and modulating local neurotransmitter signaling, BPC-157 helps normalize exaggerated gut–brain feedback loops implicated in IBS and stress-related gut dysfunction.³⁸⁻⁴⁰

2. TB-4 (Thymosin Beta-4): The Cellular Migrator

TB-4 is an actin-binding peptide essential for wound coverage, epithelial organization, and tissue architecture.⁴¹

Actin-Mediated Epithelial Repair

TB-4 regulates cytoskeletal dynamics that allow epithelial cells to migrate efficiently and cover denuded mucosal surfaces.⁴²⁻⁴⁴

Preventing Fibrosis and Strictures

TB-4 down-regulates pro-fibrotic signaling pathways, guiding repair toward flexible tissue rather than rigid scar formation.⁴⁵⁻⁴⁷

Reducing Oxidative Spillover Damage

By limiting reactive oxygen species, TB-4 protects surrounding healthy tissue and preserves an organized repair environment.⁴⁸

3. KPV: The Precision Anti-Inflammatory

KPV is a naturally occurring tripeptide derived from alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH).⁴⁹

NF-κB Deactivation at the Source

NF-κB functions as a master inflammatory switch. In chronic gut disease, it remains persistently active. KPV selectively dampens NF-κB signaling, reducing TNF-α and IL-6 output without suppressing protective immune function.⁵⁰⁻⁵²

Microbial Signal Control

KPV exhibits antimicrobial activity against opportunistic organisms such as Candida albicans, reducing microbe-driven inflammatory amplification.⁵³⁻⁵⁵

Deep Tissue Penetration

Its small molecular size allows KPV to penetrate beyond the mucosal surface, making it relevant for transmural inflammation.⁵⁶

4. GHK-Cu: The Genetic Reset

GHK-Cu is a copper-binding tripeptide involved in tissue regeneration, stem-cell signaling, and gene-expression normalization.⁵⁷

Stem-Cell Activation and Replacement

GHK-Cu stimulates local stem-cell proliferation and differentiation, restoring epithelial turnover and replacing dysfunctional cells.⁵⁸⁻⁶⁰

Gene-Expression Normalization

GHK-Cu influences thousands of genes involved in inflammation, remodeling, and repair, shifting tissue from chronic defense toward coordinated reconstruction.⁶¹⁻⁶³

Structural Collagen Support

GHK-Cu promotes balanced collagen synthesis, supporting long-term flexibility without excessive scarring.⁶⁴⁻⁶⁶

The Integrated “KLOW” Effect

KPV quiets inflammatory signaling (the firefighter)

BPC-157 restores blood flow and seals the barrier (the plumber)

TB-4 directs cell migration and limits fibrosis (the contractor)

GHK-Cu normalizes genetic repair programs (the architect)

Rather than forcing the gut to behave differently, KLOW restores the biological conditions required for healing to complete.⁶⁷⁻⁶⁸

References (AMA Style)

- Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427-434.

- Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713-1725.

- Chang JT. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1465-1478.

- Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799-809.

- Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:9-20.

- Rieder F, et al. Fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:340-350.

- Neurath MF. Host–microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713-726.

- Sikiric P, et al. BPC-157 and gastrointestinal healing. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1612-1632.

- Sikiric P, et al. Stable gastric pentadecapeptide BPC-157. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69:557-569.

- Goldstein AL, et al. Thymosin beta-4. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1269:97-107.

- Pickart L, Margolina A. GHK-Cu and tissue remodeling. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2018;29:1812-1836.

- Bischoff SC, et al. Intestinal permeability. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189.

- Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329-342.

- Hatoum OA, Binion DG. The vasculature and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G591-G598.

- Sturm A, Dignass AU. Epithelial restitution. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:528-537.

- Rieder F, Fiocchi C. Fibrosis in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:150-160.

- Turner JR. Tight junctions and gut permeability. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a013920.

- Camilleri M. IBS pathophysiology. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1626-1635.

- Barbara G, et al. Mechanisms in IBS. Gut. 2011;60:1525-1535.

- Mayer EA. Gut–brain interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:453-466.

- Ordás I, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606-1619.

- Colombel JF, et al. UC management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:483-490.

- Turner JR. Mucosal healing in UC. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a013912.

- Torres J, et al. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741-1755.

- Bettenworth D, et al. Fibrosis and strictures. Gut. 2019;68:1183-1194.

- Rieder F, et al. Intestinal fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:545-560.

- Sikiric P, et al. BPC-157 biology. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:BR57-BR65.

- Chang CH, et al. Angiogenesis and BPC-157. Gut. 2014;63:906-917.

- Seiwerth S, et al. BPC-157 vascular effects. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13030-13041.

- Sikiric P, et al. VEGF modulation by BPC-157. Life Sci. 2010;86:1-9.

- Vukojevic J, et al. Endothelial protection. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1-12.

- Turner JR. Tight junction regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799-809.

- Parkos CA. Tight junctions and inflammation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:460-465.

- Mankertz J, Schulzke JD. Altered permeability. Gut. 2007;56:183-190.

- Sikiric P, et al. Barrier restoration by BPC-157. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:103-113.

- Tepes M, et al. BPC-157 and epithelial repair. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:139-147.

- Mayer EA. Gut–brain axis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1877-1889.

- Bercik P, et al. Microbiota and anxiety. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:599-609.

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701-712.

- Sikiric P, et al. Neuroprotective effects of BPC-157. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:287-299.

- Goldstein AL, Kleinman HK. Thymosin beta-4. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:145-157.

- Smart N, et al. Thymosin beta-4 and cell migration. Nature. 2007;445:177-182.

- Sosne G, et al. TB-4 in epithelial repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1587-1596.

- Huff T, et al. Actin-binding peptides. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:280-286.

- Bock-Marquette I, et al. Anti-fibrotic signaling. Circ Res. 2004;94:e10-e17.

- Morris DC, et al. TB-4 and fibrosis. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2399-2407.

- Conte E, et al. Fibrosis modulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:405-415.

- Sosne G, et al. Oxidative stress modulation. Peptides. 2011;32:2200-2207.

- Brzoska T, et al. α-MSH peptides. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1155-1192.

- Getting SJ. Anti-inflammatory melanocortins. Peptides. 2006;27:321-330.

- Catania A, et al. Melanocortin system. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:564-590.

- Luger TA, et al. NF-κB modulation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:131-139.

- Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238-250.

- Haney EF, Hancock RE. Host defense peptides. Biopolymers. 2013;100:572-583.

- Ruzafa C, et al. Peptide tissue penetration. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:1-18.

- Pickart L. Human copper peptide GHK. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1980;15:292-297.

- Pickart L, Margolina A. GHK-Cu gene activation. Biogerontology. 2018;19:119-134.

- Maquart FX, et al. Copper peptides and healing. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2368-2376.

- Siméon A, et al. Stem-cell effects of GHK-Cu. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:193-197.

- Pickart L, et al. Regenerative gene networks. J Aging Sci. 2015;3:1-8.

- Pickart L. GHK-Cu and gene expression. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2018;29:1812-1836.

- Margolina A. Anti-inflammatory gene modulation. Rejuvenation Res. 2014;17:1-10.

- Maquart FX, et al. Collagen synthesis. Connect Tissue Res. 1993;29:1-9.

- Pickart L. Copper peptides in remodeling. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:163e-170e.

- Uitto J. Collagen regulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:541-548.

- Quan T, et al. Matrix remodeling. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:891-899.

- Neurath MF. Resolution biology in IBD. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:623-635.

- Rieder F, et al. Restoring intestinal homeostasis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:62-78.