Visible Aging: When Stress Kicks You in the NAD+ Levels

Executive Summary

Chronic stress is not just a psychological burden—it is a biochemical drain that accelerates cellular aging. One of its primary targets is NAD+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide), a molecule essential for energy production, DNA repair, immune regulation, and mitochondrial health. Under sustained stress, NAD+ is consumed faster than it can be replenished, impairing cellular maintenance and shifting the body into a long-term survival mode.

This depletion contributes to slower tissue turnover, chronic inflammation, accumulation of senescent (“zombie”) cells, and reduced mitochondrial output. Over time, these changes manifest as visible aging—thinner skin, wrinkles, hair thinning or graying, reduced muscle tone, lower energy, and slower recovery. Restoring NAD+ availability, particularly through efficient delivery methods, supports the body’s ability to complete repair processes, maintain cellular resilience, and resist stress-accelerated aging.

The Silent Saboteur: How Stress Drains Your Vitality and How NAD+ Fights Back

We all know the feeling of stress: the racing heart, the mental fog, and the bone-deep exhaustion that lingers long after a busy day. While stress is often framed as an emotional or psychological burden, it is also a biochemical stress test that places extraordinary demands on cellular systems.

One of the primary molecules affected by this process is NAD+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide). NAD+ functions as a central metabolic cofactor required for ATP generation, DNA repair, immune signaling, and mitochondrial maintenance. Under conditions of sustained stress, cellular demand for NAD+ rises sharply—often faster than endogenous production can keep up—leading to progressive depletion.¹–²

The Invisible Drain: Three Ways Stress Steals Your Fuel

Stress is not a single pathway; it is a convergence of DNA damage, inflammatory signaling, and metabolic strain. Each of these processes draws directly from the same finite NAD+ pool.

1. The DNA Repair “Tax” (PARPs)

Everyday stressors—including ultraviolet radiation, environmental toxins, psychological stress–induced cortisol elevation, and oxidative metabolism itself—produce DNA strand breaks.³–⁴ These breaks are not benign. If they are not repaired quickly and accurately, they interfere with normal gene expression, disrupt cell division, and force cells into emergency survival modes.

To manage this damage, cells activate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs)—enzymes that detect DNA strand breaks and coordinate repair. PARPs consume NAD+ directly as their substrate.⁵

When DNA damage is occasional, this system functions efficiently. Under chronic stress, however, PARPs remain active for extended periods.

In experimental models, sustained PARP activation has been shown to consume the majority of available cellular NAD+, in some cases accounting for up to ~80% of intracellular NAD+ utilization.⁶–⁷ When this happens, resources are diverted away from routine cellular renewal.

For the reader, this shows up as slower tissue turnover. Skin cells are replaced less efficiently, leading to thinner skin, reduced elasticity, and deeper wrinkles. Muscle fibers repair more slowly after training or daily wear, contributing to soreness that lingers. Tendons and ligaments remodel less effectively, increasing stiffness and injury risk. Even minor cuts, bruises, and aches take longer to resolve.

At the same time, cells burdened by unresolved DNA damage may enter cellular senescence—a dysfunctional state in which they no longer divide or contribute to repair but remain metabolically active. These so-called “zombie cells” secrete inflammatory cytokines and tissue-degrading enzymes into their surroundings.⁸–⁹ Over time, this background inflammation accelerates visible aging, joint discomfort, fatigue, and cognitive fog—even in people who otherwise appear healthy.

2. The Inflammation “Leaky Bucket” (CD38)

Chronic stress also keeps the immune system in a state of persistent low-level activation. This upregulates CD38, one of the body’s most powerful NAD-consuming enzymes.¹⁰

CD38 exists to generate calcium-mobilizing signaling molecules that allow immune cells to communicate, migrate to sites of injury or infection, and coordinate a response. In acute situations, this signaling is essential—it tells immune cells where to go, when to act, and when to stand down.

Under chronic psychological or metabolic stress, however, CD38 activity remains elevated even in the absence of a true threat. Immune signaling becomes continuous rather than targeted.

From a biochemical perspective, CD38 is extraordinarily NAD-intensive. Enzymatic studies show that CD38 degrades dozens to over one hundred molecules of NAD+ to generate a single downstream signaling molecule.¹¹–¹² When chronically activated, CD38 becomes a dominant drain on systemic NAD+ levels.

For the individual, this manifests as persistent low-grade inflammation. Joints feel achy without clear injury. Muscles remain tight. Recovery slows. Energy becomes less predictable. Skin may appear dull or puffy, and the body often feels as though it is perpetually “a little inflamed,” even with good diet and exercise habits.

3. The Starving “Longevity Genes” (Sirtuins)

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent regulatory enzymes that govern mitochondrial efficiency, oxidative stress resistance, metabolic flexibility, and cellular longevity pathways.¹³–¹⁴ Their activity is directly limited by NAD+ availability.

When PARPs and CD38 consume large amounts of NAD+ to manage DNA damage and immune signaling, Sirtuins are deprived of substrate. Cellular priorities shift away from maintenance and optimization and toward short-term survival.

Over time, this imbalance leads to reduced mitochondrial output, slower recovery from physical and mental stress, diminished resilience, and accelerated biological aging—even when calorie intake and exercise habits remain unchanged.

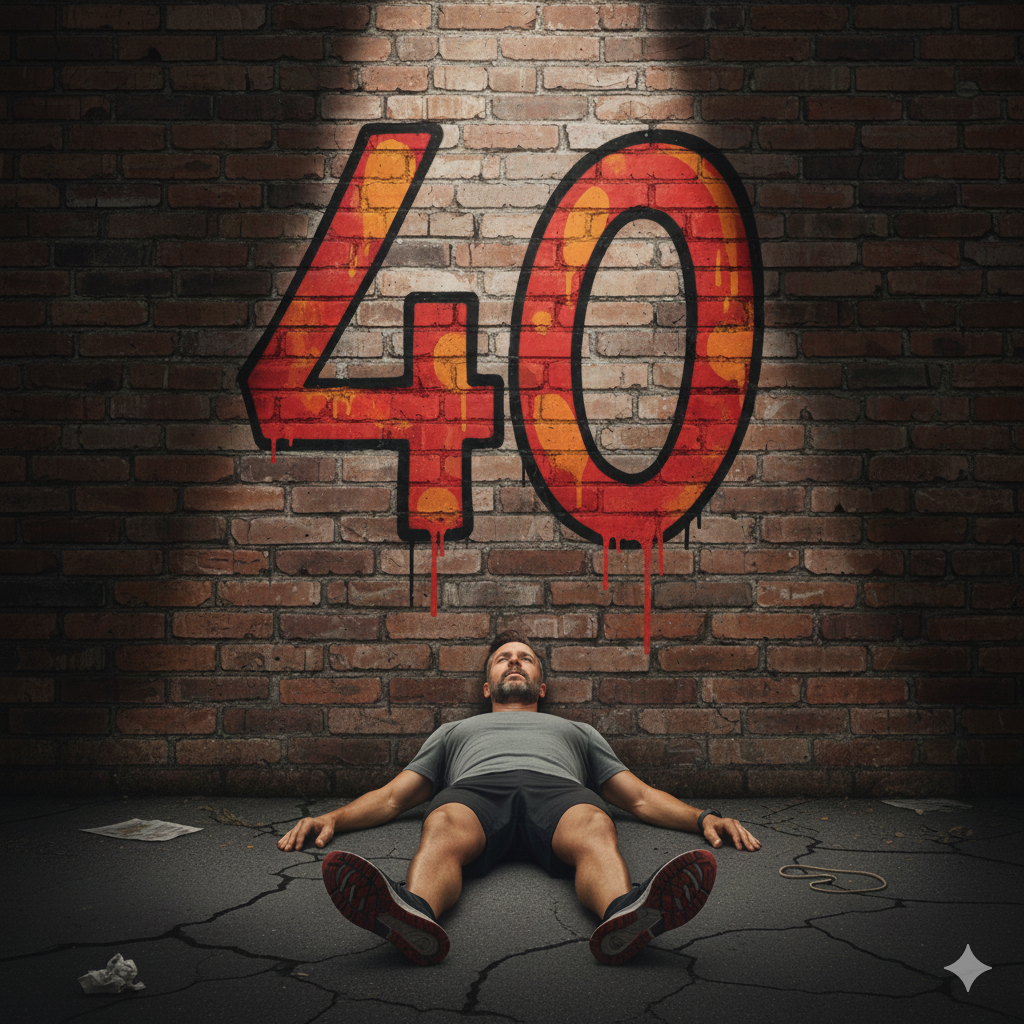

The Age Factor: Why Stress Hits Harder After 40

Aging magnifies these effects. Research consistently shows that baseline NAD+ levels decline by approximately 40–60% between early adulthood and middle age, due to both reduced synthesis and increased consumption.¹⁵–¹⁶

With smaller NAD+ reserves, stressors that are transient and recoverable in younger individuals can cause prolonged depletion later in life. Lower NAD+ increases vulnerability to stress, while stress accelerates further NAD+ loss—creating a self-reinforcing loop.

Visible Aging: When Stress Kicks You in the NAD+ Levels

This loop translates into aging people can see and feel. Collagen turnover slows, reducing skin firmness and elasticity. Wrinkles deepen. Hair follicles become less resilient, contributing to thinning and graying. Muscle tone declines despite consistent training. Energy production becomes inconsistent, and both physical and mental recovery take noticeably longer.

Stress doesn’t just make you feel older—it actively pushes your biology toward an older phenotype.

What “Looking Older” Really Means at the Cellular Level

Visible aging is biological, not cosmetic. Reduced NAD+ availability slows fibroblast activity in the skin, weakens collagen synthesis and cross-linking, impairs pigment cell resilience in hair follicles, and reduces mitochondrial density in muscle and nerve tissue.¹⁷–¹⁸

The result is thinner skin, slower wound healing, reduced muscle firmness, diminished stamina, and less reliable energy output across multiple systems.

Fighting Back: The SubQ Advantage

If stress accelerates NAD+ loss and aging reduces baseline reserves, restoration becomes a question of delivery efficiency.

Oral NAD+ faces degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and significant first-pass metabolism in the liver. Even precursor compounds must pass through these barriers before contributing meaningfully to intracellular NAD+ pools.

| Delivery Method | Estimated Bioavailability | Practical Outcome |

| Oral NAD+ | <5–10% | Extensive degradation |

| Oral NMN / NR | ~10–20% | Limited by first-pass metabolism |

| Subcutaneous (SubQ) | ~75–90% | Rapid systemic availability¹⁹ |

A 500 mg oral dose may yield ~25 mg systemically, while a 100 mg SubQ administration can deliver ~75–90 mg—allowing cells to rapidly replenish depleted NAD+ pools and address accumulated repair demands.

The End Result: Reclaiming Your Resilience

Restoring NAD+ availability does not act as a stimulant. Instead, it allows the body to resolve the backlog of unfinished maintenance created by chronic stress.

DNA repair processes can complete efficiently, reducing the accumulation of senescent cells that drive inflammation. Neuroenergetic support improves in the brain, often translating into clearer thinking and improved stress tolerance. Mitochondrial efficiency rebounds, supporting stamina, recovery, and metabolic stability.

When stress no longer monopolizes your cellular currency, the body shifts from survival mode back into maintenance and optimization mode. The result is not the absence of stress—but the ability to process it without paying for it later in accelerated aging.

References

- Verdin E. NAD⁺ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2015;350(6265):1208–1213.

- Cantó C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J. NAD⁺ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):31–53.

- Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715.

- Hoeijmakers JHJ. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1475–1485.

- Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. The diverse biological roles of PARPs. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(5):229–235.

- Berger NA. Poly(ADP-ribose) in the cellular response to DNA damage. Radiat Res. 1985;101(1):4–15.

- Bai P, et al. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Metab. 2011;13(4):461–468.

- Campisi J. Cellular senescence and aging. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705.

- Coppé JP, et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:99–118.

- Camacho-Pereira J, et al. CD38 dictates age-related NAD decline. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1127–1139.

- Aksoy P, et al. Regulation of intracellular NAD levels by CD38. Biochem J. 2006;396(3):495–503.

- Chini CCS, et al. CD38 as a regulator of NAD metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(12):849–857.

- Imai S, Guarente L. NAD⁺ and sirtuins in aging. Cell. 2014;159(1):47–62.

- Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295.

- Zhu XH, et al. Age-dependent decline in NAD⁺ metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;21(3):449–458.

- Massudi H, et al. Age-associated changes in NAD⁺ metabolism. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42357.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of collagen in skin aging. Dermatoendocrinol. 2015;7(1):e968230.

- López-Otín C, et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217.

- Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and NAD⁺ metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:115–130.