When to Use KPV vs. KLOW

Understanding When to Calm Inflammation—and When to Rebuild Tissue

Executive Summary

Many chronic health problems persist not because tissue is permanently damaged, but because inflammation never fully shuts off. Other problems exist because tissue has been structurally injured and cannot properly repair itself without help.

That distinction matters.

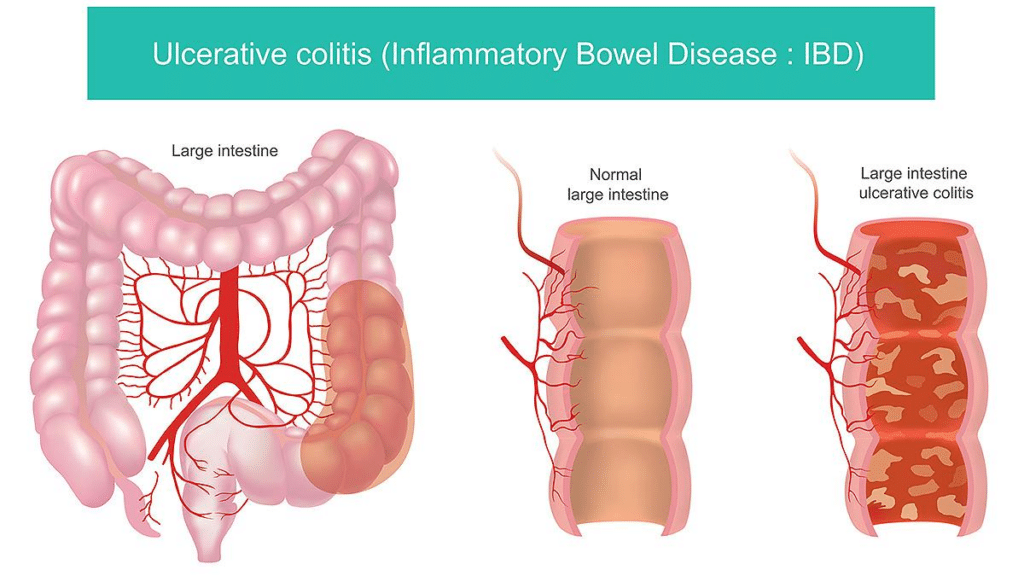

KPV is best suited for conditions driven by immune overactivation, microbial imbalance, and ongoing irritation—such as ulcerative colitis flares, inflammatory IBS, eczema, rosacea, and recurrent yeast- or bacteria-associated skin issues. It works by calming inflammatory signaling and restoring immune balance without stimulating tissue growth.

KLOW, a blend of KPV with BPC-157, TB-4/TB-500, and GHK-Cu, is designed for true tissue repair—including tendon and ligament injuries, post-surgical healing, chronic joint damage, and age-related repair decline. It activates multiple rebuilding pathways at the same time.

Choosing between them is not about “stronger versus weaker.” It is about whether the body needs to quiet inflammation or rebuild damaged tissue.¹⁻³

When the Body Is Stuck in an Inflammatory Loop

Many people experience symptoms that flare repeatedly even though no new injury has occurred. Ulcerative colitis and inflammatory-type IBS are clear examples. The intestinal lining may not be actively ulcerated, yet inflammatory signaling remains elevated, leading to urgency, cramping, bloating, and unpredictable flares. Research shows that in these states, immune signaling interferes with the gut’s ability to complete its normal repair cycle.⁴⁻⁶

The same pattern appears in the skin. Eczema, psoriasis, and rosacea are not caused by missing tissue. Instead, immune cells in the skin remain chronically activated, producing redness, itching, burning, and sensitivity. The skin is capable of normal turnover, but inflammation repeatedly disrupts the process.⁷⁻⁹

KPV fits these situations because it acts as a regulatory peptide, helping suppress excessive inflammatory cytokine activity and normalize immune behavior rather than forcing growth or structural repair.¹⁰⁻¹²

What Candida and Staph Mean in Everyday Life

Microbes such as Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus often sound abstract, but they are involved in very common problems.

Candida albicans is a yeast that normally lives in the gut and on the skin. When it overgrows, it is associated with recurrent vaginal yeast infections, oral thrush, anal itching, bloating, gas, and worsening gut symptoms in people with inflammatory bowel conditions.¹³⁻¹⁵

Staphylococcus aureus commonly contributes to recurrent boils, folliculitis, infected eczema patches, and skin that repeatedly becomes red, swollen, or slow to heal. In people with compromised skin barriers, staph can perpetuate inflammation even without obvious infection.¹⁶⁻¹⁸

KPV is unusual among peptides because it has demonstrated direct antimicrobial activity against both Candida and Staph, while also reducing the inflammatory response those organisms provoke.¹⁹⁻²¹ The other peptides in KLOW do not directly address this microbial-driven irritation.

Why Growth and Repair Signals Can Be the Wrong Tool

Peptides such as BPC-157 and TB-4, included in KLOW, stimulate angiogenesis, cell migration, and tissue remodeling. These effects are extremely useful when tissue has been torn, surgically cut, or chronically damaged.²²⁻²⁴

However, many inflammatory conditions do not require rebuilding. In those cases, adding growth signals can be unnecessary or even counterproductive. In individuals with a history of cancer or concern about abnormal cell growth, clinicians often prefer to avoid peptides that stimulate new blood vessel formation.²⁵⁻²⁶

KPV does not stimulate angiogenesis and does not promote tissue proliferation. Its role is to restore balance, not accelerate growth.

Cost, Simplicity, and Clarity of Response

KLOW contains advanced peptides such as TB-4 and GHK-Cu, which support collagen remodeling and tissue restructuring but also increase cost.²⁷⁻²⁸

For someone dealing primarily with ulcerative colitis flares, stress-driven gut inflammation, or persistent facial redness, those rebuilding pathways may offer little additional benefit. In these cases, KPV alone is often sufficient and easier to evaluate because fewer biological signals are being introduced.²⁹

Athletes and Regulatory Reality

For competitive athletes, this distinction is critical. BPC-157 and TB-500 are prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency, meaning their use can result in disqualification.³⁰ These peptides have also received increased scrutiny from the Food and Drug Administration in compounding contexts.³¹

KPV, as a naturally occurring tripeptide fragment, does not fall into the same category as systemic repair peptides and is generally viewed as lower risk from a regulatory standpoint, though rules should always be verified.³²

When KLOW Is the Better Choice

KLOW is most appropriate when the problem is structural rather than inflammatory. Examples include tendon tears, ligament injuries, post-surgical recovery, chronic joint degeneration, and age-related declines in tissue repair capacity. In these situations, calming inflammation alone is not enough—the body needs coordinated rebuilding signals.²²⁻²⁴

Final Takeaway

If symptoms show up as flares, redness, irritation, gut upset, or immune overreaction, KPV is often the cleaner and more appropriate starting point. It aligns well with conditions such as ulcerative colitis, eczema, rosacea, yeast-related issues, and recurrent inflammatory skin problems.

KLOW is not “better.” It is broader—designed for rebuilding when something is broken.

The right choice becomes clear once you identify whether the body needs to calm down—or rebuild.

References

- Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):428-435.

- Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420(6917):846-852.

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(9):617-629.

- Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448(7152):427-434.

- Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1713-1725.

- Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(5):329-342.

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1483-1494.

- Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Immune pathways in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):S43-S54.

- Draelos ZD. Rosacea: pathogenesis and management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(5):17-22.

- Catania A, et al. The melanocortin system in inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(1):23-29.

- Getting SJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of α-MSH fragments. J Immunol. 1999;162(12):7446-7453.

- Scholzen T, Luger TA. Neutralization of inflammation by melanocortins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;994:162-175.

- Kumamoto CA. Inflammation and Candida albicans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(9):636-646.

- Iliev ID, et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the host. Science. 2012;336(6086):1314-1317.

- Leonardi I, et al. Fungal dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(4):475-488.

- Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(8):520-532.

- Kong HH, et al. Skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22(5):850-859.

- Nakatsuji T, et al. Antimicrobials from commensal bacteria. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(378):eaah4680.

- Cutuli M, et al. Antimicrobial activity of α-MSH fragments. Peptides. 2000;21(11):1721-1727.

- Getting SJ. Melanocortin peptides and host defense. Peptides. 2002;23(9):1653-1661.

- Luger TA, et al. Melanocortin receptors and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(3):344-349.

- Widgerow AD. Cellular mechanisms of wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(5):127e-137e.

- Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):653-660.

- Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75-81.

- Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(21):1182-1186.

- Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039-2049.

- Pickart L. Copper peptides in tissue remodeling. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19(8):969-988.

- Maquart FX, et al. Stimulation of collagen synthesis by copper peptides. Pathol Biol. 1993;41(8):647-651.

- Precision immunomodulation strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(10):759-776.

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Prohibited List. Current edition.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Compounding and peptide-related guidance. Current publications.

- Strand FL. Neuropeptides: regulators of physiological processes. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(3):1133-1180.